- Islam Arrives

- Muslims During The Tang Dynasty (618-907)

- Muslims During The Song Dynasty (960-1279)

- Muslims During The Yuan Dynasty (1271–1368)

- Muslims During The Ming Dynasty (1368-1644)

- Muslims During The Qing Dynasty (1644-1912)

- Muslims In The Republic Of China (1911-1949)

- Muslims In The People’s Republic Of China (After 1949)

- References

Islam Arrives

During the Caliphate of Uthman

Islam came to China within a few decades after the death of Prophet Muhammad ﷺ. According to legendary accounts of Chinese Muslims, the Sahabi, Saʽd ibn Abi Waqqas رضي الله عنه was sent to China during the caliphate of Uthman ibn Affan رضي الله عنه.

Secular historians dispute the story of whether Saʽd ibn Abi Waqqas actually came to China. Regardless, they agree, and there is considerable evidence that early Muslims did arrive in the 7th century, i.e., the first few decades of the Islamic era.

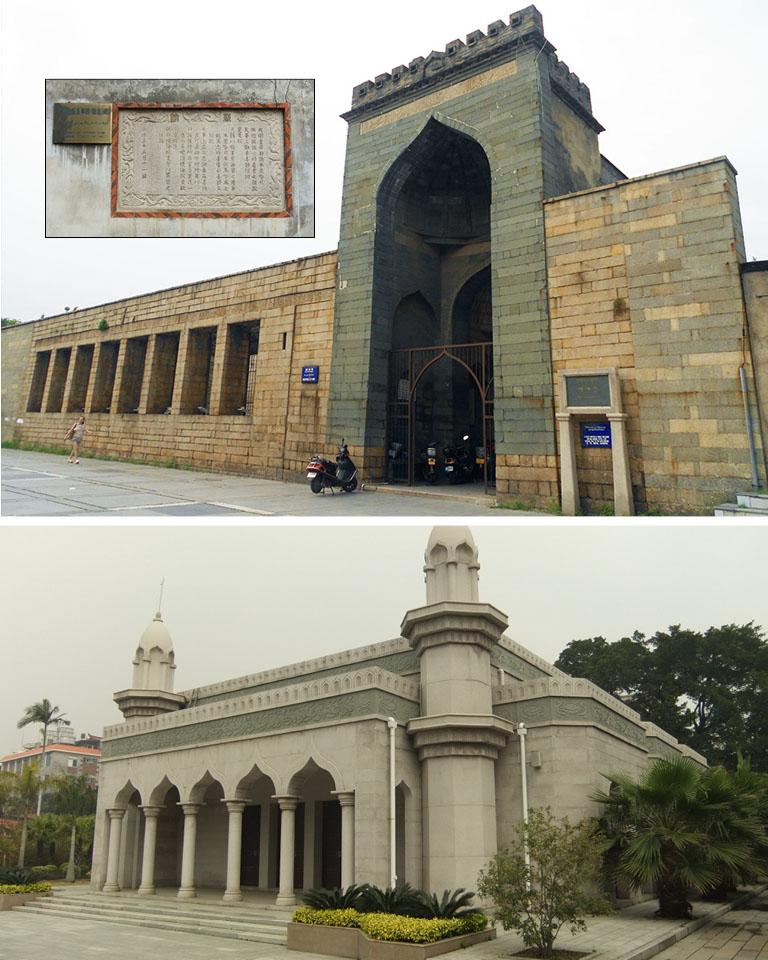

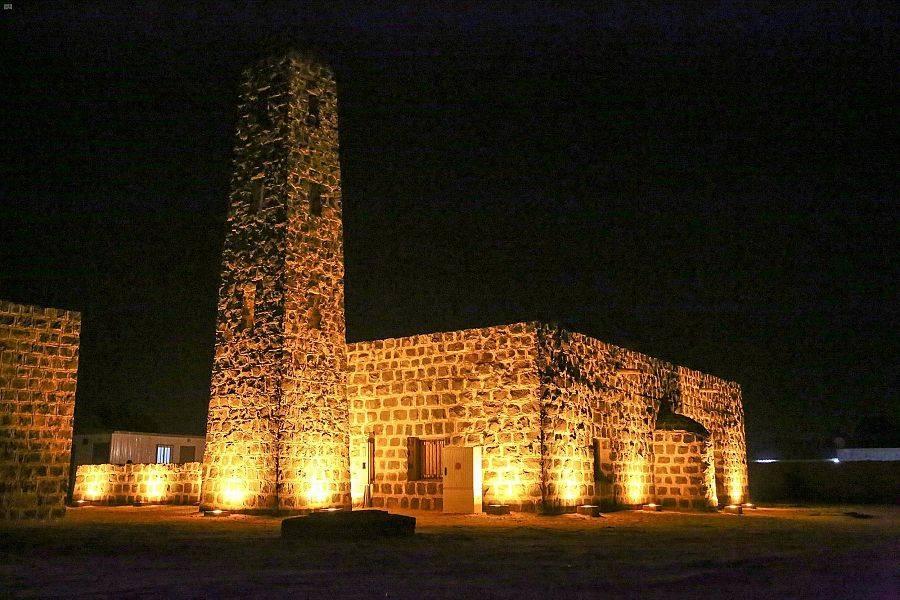

According to old Chinese Muslim manuscripts, the first masjid, the Great Mosque of Canton, was built by Saʽd ibn Abi Waqqas in Guangzhou in the 7th century. The masjid went through several renovations in history. The earliest surviving structure is a tower. The masjid is also popularly known as the Lighthouse Mosque.

Another masjid, the Great Western Mosque of Ch’ang-an (Xi’an) is said to have been built around 742. However, in the 1930s, Claude L. Pickens, an American Christian missionary to Muslims of China, found an inscription in the masjid that had a building permit of the year 705.

According to another legendary account, the Sahabi, Saʽd ibn Abi Waqqas and a group of companions first came to China from Abyssinia, after the first hijrah, during the lifetime of the Prophet ﷺ. Saʽd then came again during the caliphate of Uthman رضي الله عنه.

According to another legendary account, the Sahabi, Saʽd ibn Abi Waqqas and a group of companions first came to China from Abyssinia, after the first hijrah, during the lifetime of the Prophet ﷺ. Saʽd then came again during the caliphate of Uthman رضي الله عنه.

The Great Mosque of Canton in Guangzhou is said to have been first built by Sa’d ibn Abi Waqqas.

The only surviving structure from the original Guanghzhou mosque

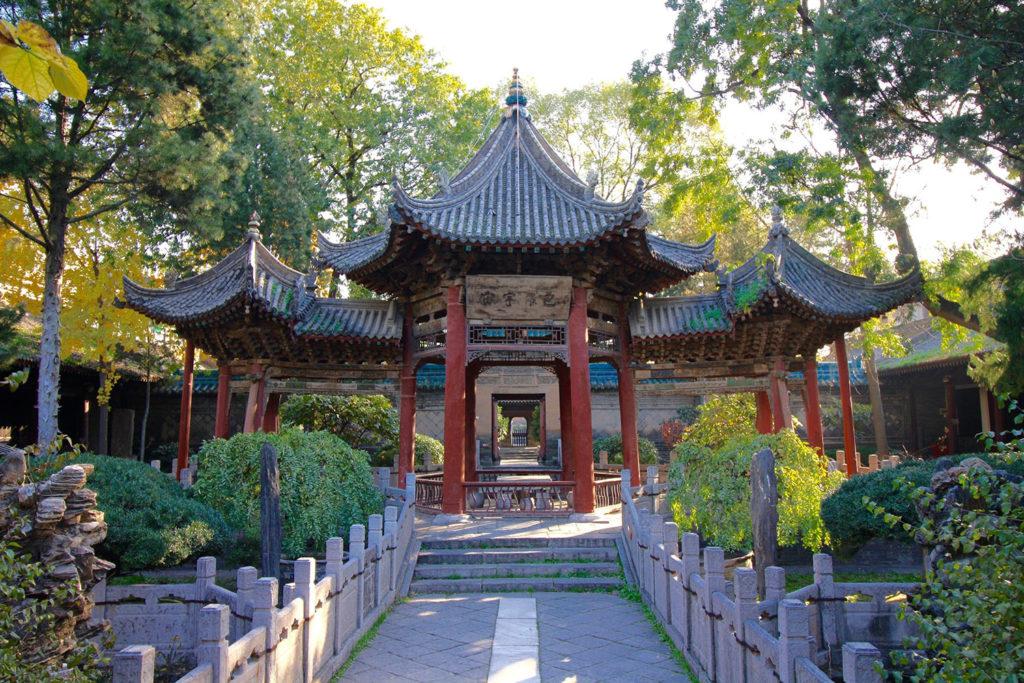

The Great Western Mosque of Xian, originally built in 742CE, but rebuilt during the Ming dynasty

Emperor’s Dream About Muslims

According to the legends, Chinese emperor T’ai Tsung (598-649 CE) of the Tang dynasty saw a dream of “a turbaned man and monsters.”

“The man in the turban, with his hands clasped and murmuring prayers, pursued the monsters… To look on, he [had] indeed a strange countenance, totally unlike ordinary men; his face was the color of black gold… his moustache and beard were cut… short and even; he had phoenix eyebrows, and high nose and black eyes. His clothes were white and powdered, a jeweled girdle of jade encircled his loins, on his head was… a cloth turban like a coiled dragon.

“His presence was awe-inspiring… When he entered he knelt towards the West, reading the book he held in his hand. When the monsters saw him they were at once changed into… proper forms, and in distressful voices pleaded for forgiveness. But the turbaned man read on for a little, till the monsters turned to blood and at last to dust, and at the sound of a voice the turbaned man disappeared.”

The court interpreter explained to the emperor that the man in the dream was, “a Muslim from the West (Arabia) where a great sage had been granted a revelation from God in the form of a book. As for the monsters, they were symbols of evil influences at work in the world — which only the Muslims could destroy.”

❝

…a Muslim from the West where a great sage had been granted a revelation from God in the form of a book

At that, a prince at the court spoke up and said: “I have heard well of these Muslims. They are straightforward and true, gracious and loyal. Throw open the pass, let communications be unhindered… and by so doing encourage peace. I beseech you to issue a decree and to send an ambassador across the western frontiers to the… Muslims, asking him to send a sage to deal with the evils that threaten, that the country may be at peace!”

However, another story about the emperor’s dream is also mentioned for Buddhism, which casts doubt on the narrative.

When the envoy of Saʽd ibn Abi Waqqas arrived in 651, Emperor Gaozang (648-683) received the invitation to Islam diplomatically. Perhaps, in recognition of the growing power of Islam, he welcomed the Muslims and allowed the construction of the first mosque in Guangzhou.

It appears that Guangzhou was selected for Muslim traders sailing on the emerging trade route. The masjid, which went through several renovations in history, still exists today.

Muslims During The Tang Dynasty (618-907)

Flag of the Tang Dynasty

❝

The Tang Emperor respected the teachings of Islam and allowed Muslims to practice their faith.

The Traders

Early Muslim settlers constituted a floating rather than a fixed element of the population, coming and going between China and the West by the oversea or the overland routes.

It appears then that the building of the masjids and the presence of Islam in China during this early period was more of a facilitation for Muslim traders traveling through or settling temporarily in China, and this appears to be restricted to Guangzhou in the south east of China.

In the northwest, however, the story was different.

Umayyad Battles Against China

Umayyads ruled the Islamic world in the early 8th century and some fierce military expeditions pit the Muslim armies against those of the Tang empire. Muslims had expanded into the lands surrounding China, popularly known in Arabic sources as ma waraa an-nahr (what lies beyond the river) or in Roman sources as Transoxiana (Central Asia that includes Uzbekistan, Tajikistan, Kazakhstan, and Kyrgyzstan).

Qutaybah ibn Muslim, an Umayyad general and governor of Khurasan under Caliph al-Walid ibn Abdulmalik, expanded into these territories with successful military campaigns. However, due to internal conflicts after the death of Caliph al-Walid and a rebellion against the caliphate, Qutaybah was killed.

After the death of Qutaybah, Muslim authority weakened in these territories and, with help from the Tang emperor, the previous king who had sought refuge in China recaptured some of these lands.[1]

❝

Umayyads ruled the Islamic world in the early 8th century and some fierce military expeditions pit the Muslim armies against those of the Tang empire

Nevertheless, by the end of the Umayyad period (750), most of Transoxania – one of the wealthiest lands of the medieval world, thanks to its extensive trade with China largely in silk, and Eastern Europe in such goods as furs, amber, honey, and walrus ivory – had been incorporated into the Islamic realm.

This conquest, however, put the Muslims on a collision course with China, which had made its presence felt in these areas as early as the second century B.C. During the Tang dynasty, commercial and diplomatic links between China and Transoxania were quite strong.

[1] The Fergana Valley, especially, could not be recaptured until the Abbasids came to power.

The Battle Of Talas And The Abbasid Victory

Read the full article: The Battle Of Talas

The Battle of Talas led to the spread of Islam in Central Asia and the introduction of Chinese paper-making technology in the Islamic world.

According to Muslim sources, the Chinese had arrived with an army of 100,000 (30,000 according to Chinese sources) near the Talas river. Chinese annals say the fighting lasted for five days, while Arabic records are inconclusive. The result of this epic encounter, however, is unanimously attested: The Muslims utterly destroyed the Chinese army. In the words of Imam al-Dhahabi, “Allah cast terror into the hearts of the Chinese. Victory descended, and the disbelievers were put to flight.”

The victory permanently ended Chinese influence in the region. The Abbasids ruled for the next 400 years and Central Asia has since been predominantly Muslim. The Tang empire was going through internal rebellion and conflicts in China, which made them retreat and not come back to vie control in Central Asia.

Description Of Muslims In Tang Manuscripts

Du Huan, a Chinese prisoner taken to Baghdad after the Battle of Talas, gave a good description of Muslims in the 8th century, which was recorded in the Tongdian (801CE) [2]:

❝

“The men have high noses, are dark, and bearded. The women are very fair [white] and when they go out they veil the face. Five times daily they worship God [Tianshen]. They wear silver girdles, with silver knives suspended. They do not drink wine, nor use music… Every seventh day the king sits on high, and speaks to those below saying: ‘Those who are killed by the enemy will be reborn in Heaven above; those who slay the enemy will receive happiness.’”

According to other reports, including one by al-Tabari, when an envoy of Caliph al-Walid visited Emperor Hsuan Tsung in 713CE with presents, he refused to perform the prescribed obeisance, saying: “In my country we only bow to God and never to a prince.” At first, the emperor wanted to kill the envoy. One of the ministers, however, interceded saying that “a difference in the court etiquette of foreign countries ought not to be considered a crime.”

[1] Tongdian is a Chinese institutional history and encyclopedia text written from 766-801

Muslims During The Song Dynasty (960-1279)

Flag of the Song Dynasty

Trade was booming and many Arab and Persian merchants flocked to Guangzhou where the office of the Director General of Shipping was constantly under Muslim management, due to their law-abidingness and self-disciplined nature.

Abul-Abbas al-Hijazi, a prosperous twelfth-century merchant who spent many years in China, had seven sons whom he posted in seven different commercial centres from his base in Yemen thus establishing a successful trading network after the loss of all but one of his twelve ships in the Indian Ocean.

❝

Muslims in China dominated foreign trade and the import/export industry to the south and west

In 1070, the Song emperor Shen-tsung invited 5,300 Muslim men from Bukhara to settle in China. The emperor sought their help in his campaign against the Liao empire in the northeast. The object was to create a buffer zone between the Chinese and the Liao.

In 1080, 10,000 Arab men and women migrated to China on horseback and settled in different provinces of the north and north-east.

Awareness of Islam spread during this period as Muslims multiplied and became more dominant. Chinese literature mentioning the stories of Ibrahim, Yusuf and Ismaeel were influenced by Islamic sources and not Biblical ones.

Description of Muslims in Song manuscripts

The description of Muslims during the Song dynasty is strikingly similar to the account provided by Abu Zaid in the 9th century.

Referring to 1192, Zhu Yu and Yue Ke describe foreigners living in Guangzhou who have Muslim customs. Zhu Yu writes:

❝

“In the foreign quarter in Guangzhou reside all the people from beyond the seas. A foreign headman [fanzhang] is appointed over them and he has charge of all public matters connected with the quarter. He makes it his special duty to urge the foreign traders to send tribute. When a foreigner commits an offence anywhere, he is sent to Guangzhou, and if the charge is proved he is sent to the foreign quarter [and whipped].”

Zhu Yu also writes:

❝

“Even now foreigners are not just forbidden from eating pork… Even now, foreigners will not eat any of the six domestic animals not slaughtered by their own hand. As for fish and turtles, they eat all.”

The situation for foreigners, in particular Muslims, had hardly changed since the Tang. But by now they were settlers, not aliens. They had mosques in most of the big cities, in Guangzhou, Quanzhou, Xi’an, Hangzhou, Yangzhou; and almost certainly in Kaifeng, Beijing, Ningbo, Dingzhou and elsewhere. There were special Muslim cemeteries in Guangzhou, Quanzhou and Hangzhou.

Song sources also refer to Muslims as “five generation foreign guests.”

THE MONGOLS

Muslims During The Yuan Dynasty (1271–1368)

❝

Muslims were ranked above the Chinese, second in status only to the Mongol overlords themselves.

With the coming of Mongols, life changed for Muslims in China.

The Mongols transported tens of thousands of artisans and technicians of various kinds from Persia and Central Asia all the way to Mongolia and Beijing in north China. Many Muslims were amongst them. Muslim soldiers also became an important part of the Mongol armies.

It was in the Mongol Yuan period that the largest influx of Muslims occurred. Additionally, a Mongol prince Ananda converted to Islam, together with tens of thousands in the area.

Muslim traders also moved into other parts of China from the port cities of Guangzhou and Quanzhou.

Mongols Divide and Rule

The Mongols organized society into four main classes: Mongols, Semuren (Muslims fell in this category), Hanren (North Chinese) and Nanren (South Chinese).

The Muslims were ranked above the Chinese, second in status only to the Mongol overlords themselves. Several Muslims reached high ranks in the Mongol government. Muslims were officials, military officers, financial advisers, engineers, cartographers and architects, astronomers, physicians and pharmacists, tax collectors, customs officers and trading middlemen.

Chinese Dislike of Muslims

The division into classes appears to be a strategic move of the Mongols to subjugate the local population. At the same time the Mongols imported Central Asian Muslims to serve as administrators in China, the Mongols also sent Han Chinese and Khitans from China to serve as administrators over the Muslim population in Bukhara in Central Asia, using foreigners to curtail the power of the local peoples of both lands.

The Chinese hated them for their support of the Mongols, and for their financial role as tax collectors and trading agents of the Mongols. It is only during this period that we find Chinese sources ascribing racist and derogatory descriptions to Muslims.

Oppression and Rebellion

The Mongols were not always friendly to Muslims. The rulers granted a sort of monopoly to foreigners whom at one and the same time they despised, exploited and protected.

In fact, for a short time (1280-87) the Mongol ruler forbid (halal) ritual slaughter and circumcision for Muslims and Jews. However, because of the damage to trade this produced, this oppression was canceled.

Towards the end of the Mongol Yuan period more restrictions were placed on Muslims, perhaps to win the support of the local Chinese. Persecution and corruption became so severe that top Muslim generals from the Mongol army joined the Han Chinese in rebelling against the Mongols. The Ming founder Zhu Yuanzhang had Muslim generals like Lan Yu who fought and defeated the Mongols in combat.

Ibn Battuta’s Journey To China

Read the full article: Ibn Battuta’s Adventurous Journey To China

Ibn Battuta (1304-1369) was a noted explorer and traveler born in Morocco into a family of judges. He served as a Qadi (judge) for eight years in the Sultanate of India under Sultan Muhammad Tughlaq (1326-51). The Sultan assigned him a mission to China in 1341 as an ambassador to meet the most powerful ruler in the world, the Mongol Emperor of China.

After an adventurous journey, Ibn Battuta finally arrived at the port of Madinat al-Zaitun (Quanzhou) in 1345. He described al-Zaitun as housing one of the largest ports in the world with about a hundred junks (Chinese sailing ships) that could not be counted for multitude. Every city had a separate Muslim quarter where merchants and their families lived in an honoured and respected manner with their own mosques, hospitals and bazaars.

Ibn Battuta had arrived in the last peaceful years before the collapse of the Mongol (Yuan dynasty) rule. He noted, “China is the safest and most agreeable country in the world for the traveler. You can travel all alone across the land for nine months without fear, even if you are carrying much wealth.”

He declared that of all people the Chinese were the most skillful in the arts and possessed greatest mastery of them.

THE PEAK

Muslims During The Ming Dynasty (1368-1644)

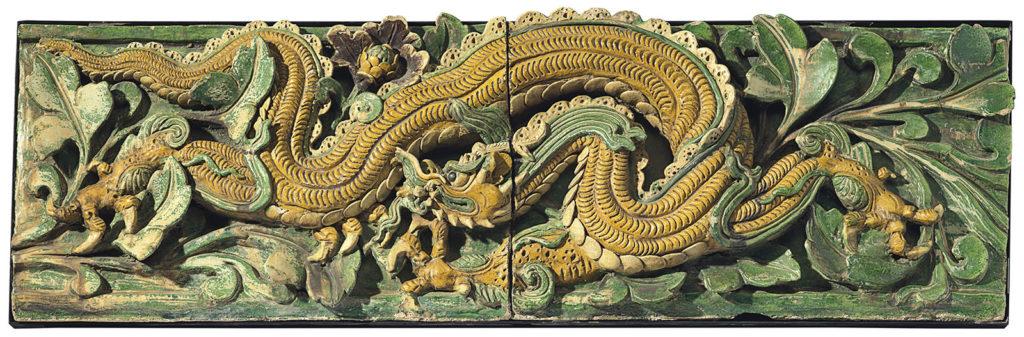

A Two-part glazed pottery ‘dragon’ tile from the Ming Dynasty. Source: Christie’s

Perhaps due to their support of the Ming rebellion against the Mongols, Muslims enjoyed special protection and treatment in the Ming empire. Islam and Judaism were respected, but Christianity and Manichaeism were not.

The Emperor Builds Mosques

The founder of the Ming dynasty, Hongwu Emperor, Zhu Yuanzhang, ordered the building of several mosques in southern China, and wrote a 100-character praise on Islam, Allah and the Prophet Muhammad ﷺ. He had over 10 Muslim generals in his military. The Emperor built mosques in his capital Nanjing and in Yunnan, Guangdong and Fujian. Large numbers of Muslims moved to Nanjing during his rule. He ordered that inscriptions praising Muhammad ﷺ be put in mosques.

❝

[The emperor] wrote a 100-character praise on Islam, Allah and the Prophet Muhammad ﷺ

Integration into Chinese Culture

The Ming dynasty saw a rapid decline in Muslim population in the seaports. This was due to the closing of all seaport trade with the outside world except for rigid government-sanctioned trade.

Many Muslims from Central Asia who were moved to China during the Mongol period settled down and took Chinese surnames. It was during the Ming dynasty that Muslims first adopted and integrated into Chinese culture. Many became fluent in Chinese and adopted Chinese names. The capital, Nanjing, became a center of Islamic learning.

Communities with Ahung (Imam) leaders flourished. Muslims were able to win prestigious degrees to become magistrates and education officials. They still kept their special trades as beef and mutton growers, importers and transporters.

Muslim customs of dress and food went through a synthesis with Chinese culture. The Islamic modes of dress and dietary rules were maintained within a Chinese cultural framework. Chinese Islamic traditions of writing began to develop, including the practice of writing Chinese using the Arabic script (xiaojing) and distinctly Chinese forms of decorative calligraphy. The script is used extensively in mosques in eastern China.

Mosque architecture began to follow traditional Chinese architecture. A good example is the Great Mosque of Xi’an, whose current buildings date from the Ming dynasty. Western Chinese mosques were more likely to incorporate minarets and domes while eastern Chinese mosques were more likely to look like Chinese.

Forced Ethnic Assimilation

Although Islam was tolerated, the early policy towards ethnic minorities was of integration through forced marriage. After a century of Mongol rule, the Ming wanted to bring back the domination of Han Chinese. Members of other ethnic groups were required by law to intermarry. So, Hui Muslims had to marry Han since they were of different ethnic groups, with the Han often converting to Islam. These regulations, like the ones in the Tang and Song, were soon abrogated or ignored.

Da’wah Activity and Literature

China and the Muslim world had contact in the Ming period. The first written record of Chinese Muslims performing the Hajj is from this period. Some pilgrims left accounts of their difficult journeys in Chinese. The knowledge of the Muslim world is reflected in works as the great Ming geography, which contains relatively precise information about cities, including Makkah and Madinah, some of which may have been gathered on the naval expeditions of Zheng Ho, a Muslim admiral in the service of the Ming.

Islamic propagators continued to visit during this period, perhaps bringing in a variety of beliefs and philosophies.

It was during the Ming Dynasty that many Arabic books – particularly those of a scientific nature – were translated into Chinese. Islamic medicine and astronomy were now influential in China.

Islamic Books in Chinese

Wang Daiyu, a Muslim scholar of Arab descent, wrote perhaps the first original Islamic literature in Chinese. He authored the five-volume True Explanation of the Correct Religion (Zhengjiao Zhenquan)in 1642, two years before the end of the Ming dynasty.

Wang saw the need for Islamic works in Chinese instead of depending solely on Arabic ones. He went on to write Qingzhen Da Xue (The Great Learning of Islam) and Xizhen Zhengda (Rare and True Answers).

Wang, who knew Chinese, Persian and Arabic and had studied Confucianism, used Chinese classical texts to explain Islam. He was critical of Buddhism and Taoism, while citing Confucian ideas which agreed with Islam in order to explain it.

Other authors like Ma Zhu and Liu Zhi also wrote several books on Islam, but sometimes using and mixing Confucian ideas with Islamic teachings.

Muslims During The Qing Dynasty (1644-1912)

Flag of the Qing Dynasty

The period during the Qing dynasty was marked by war, rebellion and conflicts. Muslims split into rival, sometimes ethnic and sectarian, factions depending on whose side of the war they were fighting.

With the fall of the Ming dynasty, there was a power vacuum, and western regions of China were left to themselves. It took some time for the Qing to settle and start retaking the territories under Ming. The Qing were ethnically Manchus, a minority among the Han Chinese.

Introduction of Sufism in China

Afaq Khoja (1626-1694) is generally credited with the influence of Sufism in China. His two spiritual descendants, Ma Laichi and Ma Mingxin, founded the two dominant schools of Chinese Sufism – Khufiyya and Jahriyyah. Another Chinese Sufi master Qi Jingyi, who met Afaq Khoja when he was 16, introduced and spread Qadriyyah in different parts of China.

East Turkestan Falls to Qing

For the first time, in 1759, a Chinese dynasty conquered the land of Uyghurs. The Qing overthrew the Dzungar Khanate to take control of the Tarim Basin where Uyghurs, the Turkic Muslims lived. While we will explore the history of Uyghurs in another article in-sha Allah, it is relevant to mention at this point that the current borders of China are based on the Qing dynasty’s expansions. Although the Mongols also briefly took over these areas, the Mongols were never Chinese. The Qing renamed this territory as the Xinjiang (new territories).

Muslim Rebellions

In the beginning, when Qing had invaded, Muslims loyal to the Ming led a rebellion to drive out the Qing and restore the Ming prince. The rebellion was joined by Han Chinese and Tibetans. The rebellion was ultimately crushed.

A few years after the fall of East Turkestan, the Uyghurs revolted because of – without going into much detail – the corruption and oppression to which the Qing officials subjected them.The oppressing Qing officials included Muslims as well, unfortunately. This revolt was more of a revenge carried out against select individuals. The Qing in response killed the rebels and exiled their women.

The situation did not improve, and Uyghur’s hatred of the Manchu rule grew. Jahangir Khoja from the neighborhood Kokand Khanate attacked and was able to free Kashgar and Yarkand (parts of Xinjiang) from Qing in 1820. With the help of Hui Muslim merchants, the Qing defeated Jahangir and retook the territories in 1828.

In 1781, two rival Sufi groups – Jahriyya and Khafiyya – were involved in sectarian violence. When the fighting did not stop, Qing got involved and imprisoned some of the leaders. The Jahriyya revolted and the Qing, with help from Khafiyya, crushed the Jahriyya.

In 1862, what started as conflicts and riots between Hui Muslims and Han Chinese in some parts of China (excluding Xinjiang), blew out of proportion and turned into a full-scale revolt. The Qing had adopted an approach of segregation and division to be able to rule over the different ethnicities, because the Qing themselves were an ethnic minority ruling of a majority of Han Chinese and others.

This revolt, called as the Dungan revolt, was mostly led by Hui Muslims but it was not of a religious nature. The revolt had no clear objective and it was more of a riot against the frustrations some of the people felt under Qing rule. Hui Muslims living in unaffected parts of China were not touched by the revolt.

❝

The Qing had adopted an approach of segregation and division to be able to rule over the different ethnicities, because the Qing themselves were an ethnic minority ruling of a majority of Han Chinese and others.

While the Qing were distracted by the Hui rebels, Yaqub Beg, who had fled from the Kokand Khanate managed to take full control of Xinjiang. Yaqub Beg, who ruled for 10 years, was not particularly noble either. He slaughtered many local Uyghurs and kept them out of his administration.

The Qing, with the help of several Muslim generals and armies, crushed the revolt and reconquered Xinjiang. General Ma Anliang led an entire army composed of Chinese Muslim troops against Yaqub Beg’s Turkic Muslim forces and defeated him, reconquering Turkestan for China.

Ma Anliang led Hui cavalry troops in the slaughter of rebel Salar Muslim fighters, who had agreed to negotiate unarmed at a banquet. He lied to them, saying, “Disown me as a Muslim if I deceive you.” Although he was a Muslim, he showed no mercy to those Muslims who had rebelled against the Qing government.

Islamic Kingdom of Yunnan

Du Wenxiu, a Han Chinese whose family had embraced Islam, led a massive revolt against the Qing. He took over the city of Dali in western Yunnan in 1856 and proclaimed it the “Islamic Kingdom of Yunnan.” He held it until it fell in 1872.

Du’s Muslim name was Sulayman ibn `Abd ar-Rahman. He took the title of Qa’id Jami al-Muslimin (Leader of the Community of Muslims), but the title generally used was ‘Sultan.’ He wore Chinese clothing, mandated the usage of Arabic language, and banned pork. The Sultanate reached its peak in 1860 and enjoyed its zenith for the next eight years. During this time, Sultan Sulayman made pilgrimage to Makkah.

Du Wenxiu (Sulayman) used anti-Manchu rhetoric in his rebellion, calling for Han to join the Hui to overthrow the Manchu Qing. He called for unity between Muslim Hui and Han and was quoted as saying, “our army has three tasks: to drive out the Manchus, unite with the Chinese, and drive out traitors.” He did not blame the Han for ethnic conflicts, but blamed the Manchu rulers, saying that they were foreign to China and alienated the Chinese and other minorities. He called for the complete expulsion of Manchus from all of China in order for China to once again come under Chinese rule.

❝

The current Chinese government considers Du Wenxiu a national hero.

By 1871, the Qing had reinvigorated and planned to attack Yunnan. Another Muslim leader, Ma Rulong who had rebelled along with Du Wenxiu, had surrendered and defected to Qing. He played a critical role in fighting and defeating Du Wenxiu. Ma Dexin, a Muslim scholar, claimed that Neo-Confucianism was compatible with Islam and allowed Ma Rulong to defect and fight Du Wenxiu. Under Qing, Ma Rulong and his forces almost entirely took control of Yunnan. With the help of French support and advanced artillery, Du Wenxiu’s kingdom fell to the Qing.

The current Communist Party of China regards the Qing as foreign and Du Wenxiu as a national hero.

Muslims In The Republic Of China (1911-1949)

In 1911, the Chinese Revolution overthrew the Qing, the last imperial dynasty of China, and established the Republic of China. The first president, of the Kuomintang party, declared that the country belonged equally to the Han, Hui (Muslim), Meng (Mongol), and the Tsang (Tibetan) peoples. This improved ethnic relations in the country.

The Muslim community started rebuilding what was destroyed during the Qing period. The interaction of Muslims in China with the Muslim World also increased. By 1939, at least 33 Hui Muslims had studied at Cairo’s Al-Azhar University. Academic activities within the Muslim community also flourished. Before the Sino-Japanese War of 1937, there existed more than a hundred known Muslim periodicals. Thirty journals were published between 1911 and 1937.

Muslims served extensively in the National Revolutionary Army and reached positions of importance, like General Bai Chongxi, who became Defence Minister of the Republic of China.

The Warlord Era

During the end of its dynasty, the Qing was forced to allow provincial governors to raise their own armies. This continued in the beginning period of the Republic of China. The country was divided among military cliques and other regional factions. Muslim warlords and generals were quite powerful and played an instrumental role in the fight against the Japanese invasion in the 1930s.

Second Sino-Japanese War

In 1937, after a few years of skirmishes, Japan conquered Beijing, Shanghai, and the then Chinese capital Nanjing. The Japanese continued on a killing rampage, especially against Muslims. About 220 mosques were destroyed and countless Hui Muslims were killed. The Hui Muslim county of Dachang was subjected to slaughter by the Japanese.

❝

Muslim leaders went to the Middle East to gain backing for China

The Japanese tried to win Muslim support in the war by promising liberation and self-determination. However, Muslims did not join the Japanese and fought fiercely against the invasion. Several prominent Muslim generals played a critical role in fighting off the Japanese. Jihad was declared as obligatory by Chinese Muslims and many imams made preaching Chinese nationalism mandatory in mosques.

Imam Du Pusheng and other Muslim leaders traveled to the Middle East and other Muslim countries to gain backing for China and refute the misinformation of Japanese agents.

Japan had also by its attack on Pearl Harbour declared war on the United States. With support from the US and Russia, China defeated the Japanese and Japan formally surrendered on September 2, 1945.

East Turkestan

The stirrings of Uyghur separatism during the early 20th century were greatly influenced by the modern reform movements popular in Turkey, Russia and other parts of Europe. The birth of the Soviet Union also influenced the Uyghurs, increasing the popularity of nationalist separatist movements and the spread of the communist message.

The double taxation and oppression of the Uyghurs by the Xinjiang governor also added fuel to the fire. All these issues led to a rebellion and forming of the First Islamic Republic of East Turkestan in 1933. The original proclamation of the state was not only against the Han Chinese, but also very much against Hui Muslims who were considered foreigners.

The state did not last long as in 1934 Hui Muslim generals attacked and reconquered the territory for China.

A second East Turkestan was established with the help of Soviets in the 1940s, which also did not last more than a few years (1944-1949).

Chinese Civil War and the Muslim Role

The Civil War was fought between the ruling Kuomintang party of the Republic of China and the Communist Party. The first insurgencies of the Communist Party started in 1927 and continued till the Japanese war broke out in 1937. After that, the Civil War resurfaced in 1946. The Communist Party reached out to the Muslims for support promising religious freedom and relative independence in return. However, the promises were not honored for very long.

Muslims In The People’s Republic Of China

(After 1949)

Flag of People’s Republic of China

Founded by Mao Zedong of the Chinese Communist Party in 1949, the People’s Republic of China went through tremendous upheavals in the early years which culminated in the Cultural Revolution. The promise of religious freedom did not last, and Islam, like all other religions, was persecuted. Mosques were attacked and religious practice was restricted. Mao was a dictator who eliminated anyone who disagreed with his policies.

❝

The promise of religious freedom did not last… even common utterances, such as In-sha Allah and Alhamdulillah, could cause Muslims to be imprisoned.

Oppression During the Cultural Revolution

During the Cultural Revolution (1966-1976), Muslims of China found their religion outlawed and their religious leaders persecuted, imprisoned and killed.

All worship and religious education was forbidden, and even simple common utterances, such as in-sha Allah and alhamdulillah, could cause Muslims to be harassed, imprisoned, tortured, and in extreme cases, killed. Despite the danger, Muslims in many parts of China continued their religious studies in secret.

Mosques, as the centers of communities, were targeted by the state. Local officials throughout the country took control of mosques, appropriating their buildings and land and turning them into factories, storage areas, barns, and schools. Many were simply destroyed. In addition, deliberate efforts were made by local officials to defile the mosques and their adjacent land. For example, mosques were used to accommodate pigs, while pig bones and carcasses were thrown down the drinking wells in mosque courtyards to permanently pollute them.

Shadian Massacre

The most extreme example of state-sponsored violence against Muslims during the Cultural Revolution took place in July 1975, when Shadian, a Muslim village in Yunnan province, was completely destroyed. What happened in Shadian was so extreme that in 1979 the government officially apologized and provided compensation to the surviving residents.

Islamic Revival and Activism

When Mao died in 1976, Deng Xiaoping became the leader of the Communist Party and initiated economic and social reforms. New legislation gave all minorities the freedom to use their own spoken and written languages, to develop their own culture and education and to practice their religion.

In the years immediately after the Cultural Revolution, Muslims of China lost no time in rebuilding their devastated communities. Throughout China, Muslims slowly began to restore their religious institutions and revive their religious activities. Their first priority was to rebuild their damaged mosques. Once communities were able to pray together again, the next priority was to organize Islamic Studies classes.

As early as the 1980s, some mosques began to organize classes for girls, boys, and young adults, as well as for the older men and women of their communities who had not had the opportunity to study their religion. Beginning in the early 1990s, independent Islamic colleges were also established throughout most of China, except for Xinjiang. These schools offered a full curriculum, including classes on the Qur’an, hadith, tafsir, fiqh, Islamic history, the history of Islam in China, Arabic grammar, and Chinese language.

As early as the 1980s, some mosques began to organize classes for girls, boys, and young adults, as well as for the older men and women of their communities who had not had the opportunity to study their religion. Beginning in the early 1990s, independent Islamic colleges were also established throughout most of China, except for Xinjiang. These schools offered a full curriculum, including classes on the Qur’an, hadith, tafsir, fiqh, Islamic history, the history of Islam in China, Arabic grammar, and Chinese language.

Many graduates from these colleges go on to teach in smaller schools and establish new schools in different regions.

A growing number have also continued their Islamic studies overseas. Hundreds, if not thousands, of students have studied in Egypt, Saudi Arabia, Syria, Pakistan, Iran, Turkey, and Malaysia. Those who return to China bring back an awareness of the world and a strong foundation in Islamic studies.

Although many hope to immediately take up positions as imams in their home towns and villages, it is often the case that the religious leaders of the community, although impressed with their foreign training, want to make sure the future imams have also acquired an understanding of their own communities and their needs.

References

- Khamouch, M. (2005). Jewel of Chinese Muslim’s Heritage. Foundation for Science Technology and Civilisation.

- Hoberman, B. (1982, September/October). The Battle of Talas. Retrieved December 02, 2020, from https://archive.aramcoworld.com/issue/198205/the.battle.of.talas.htm

- Leslie, Donald. (2006). The Integration of Religious Minorities in China: The Case of Chinese Muslims. esocialsciences.com, Working Papers.

- ‘T’ang shu, Bk. 221, as quoted by Abel Remusat, Milanges Asiatiques, I. 44I. E.

- Bretschneider, On the Knowledge of Ancient Chinese of the Arabs, etc., 8; quoted by Diplomatic Missions to the Court of China: The Kotow Question I; Author(s): William Woodville Rockhill; Source: The American Historical Review , Apr., 1897, Vol. 2, No. 3 (Apr., 1897), pp. 427-442; Published by: Oxford University Press on behalf of the American Historical Association

- Armijo, J. (2008). Islam in China. In Asian Islam in the 21st Century (pp. 197-228). Oxford University Press.

- Weil, D. (2016). Islamicated China: China’s Participation in the Islamicate Book Culture during the Seventeenth and Eighteenth Centuries. Brill.

- Ke, W. (2017). Between the “Ummah” and “China”: The Qing Dynasty’s Rule over Uyghur Society in Xinjiang. Journal of Intercultural Studies, 48, 183-218.

Dr. Bilal Philips

Dr. Bilal Philips