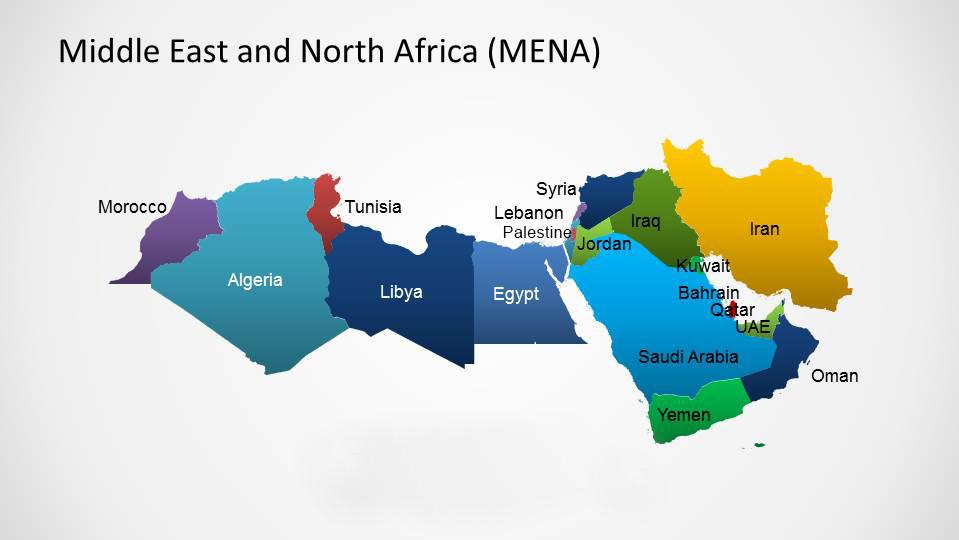

Economically, some countries in the Middle East and North Africa (MENA) region are very close to Ukraine and Russia as trade partners. As such, the effects of the crisis will impact the MENA economies, and, sadly, can have a compounding negative effect on food security and welfare across the region. This is on top of COVID-19, supply chain disruption, and country-specific domestic issues.

The main channels of impact can be divided into five categories: 1) food price shocks (especially wheat), 2) oil and gas price hikes, 3) global risk aversion (which could impact private capital flows to emerging markets as a whole), 4) remittances, and 5) tourism.

Oil and Gas Exporting Countries

Oil and gas exporting countries like Qatar, Saudi Arabia, Kuwait, Libya, and Algeria may see improvements in both fiscal and external balances and higher growth. Especially those exporting gas are likely to see a structural increase in demand from Europe, as EU authorities announced interest in diversifying their sources of energy supplies.

Moderately Affected

Non-oil producers, however, will experience negative outcomes leading to additional social stress. Remittances — especially those emanating from expatriates based in the GCC — will only very partially offset some of the hydrocarbon shock (e.g., for Jordan and Egypt), while countries that are more exposed on tourism, for example, Egypt (where Russians and Ukrainians have represented at least one-third of tourist arrivals), are projected to experience sluggishness in the sector, with some negative repercussions on employment and the balance of payments.

Hardest Hit

Finally, several MENA economies will be materially and negatively impacted by the conflict in Ukraine (e.g., Lebanon, Syria, Tunisia, and Yemen). These are the countries that primarily rely on Ukraine and/or Russia for their food imports, and particularly for wheat and cereals. The crisis is set to disrupt grain and oilseeds supply chains, increase food prices, and shoot up domestic production costs in agriculture.

Reduced yields and incomes, especially for small-scale farmers, will have adverse implications for livelihoods and likely disproportionately affect those, among the poor and vulnerable, who are dependent on farming for their income.

Lebanon imports from Ukraine and Russia over 90% of its grain and only has about a month of grain reserves.

At the top of our concerns are MENA’s already fragile countries — like Syria, Lebanon, and Yemen — where the Ukrainian crisis risks to dramatically jeopardize access to food. Syria imports roughly two-thirds of both its food and oil consumption, and most of its wheat is specifically from Russia.

Lebanon imports from Ukraine and Russia over 90% of its grain and only has about a month of grain reserves. Yemen imports about 40% of its wheat from the two countries at war. People experiencing crisis or, even worse, acute food insecurity in Yemen climbed from 15 million to over 16 million in just three months, at the end of 2021. The war in Ukraine will only worsen this already bleak dynamic in Yemen.

The compounding shock of the war in Ukraine can cause tragic outcomes in some MENA countries if humanitarian and development assistance are not scaled up in 2022. To give a sense of the magnitude, at the regional level, consider that last year the MENA region accounted for only 6% of the world’s total population, but over 20% of the world’s acutely food insecure people.

Pressure on wheat prices

In Tunisia, nearly half of the wheat imports come from Ukraine, and the Russian invasion has sent prices to a 14-year high. Even though the Tunisian state controls the price of bread, people fear they will inevitably feel the crunch.

If the price of bread goes up, it’ll mean cutbacks elsewhere.

Tunisia is highly vulnerable to such aftershocks, with a fragile economy battered in recent years by inflation and high unemployment, and saddled with large amounts of public debt. But it is far from the only country in the Middle East and north Africa that would face difficulties in the event of prolonged supply-chain disruption and price hikes.

Yemen, which has itself has been ravaged by war since 2014, imports almost all its wheat, with more than a third coming from Russia and Ukraine. It is highly dependent on bread, which is thought to make up over half of the calorie intake for the average household.

Lebanon, a country in the grips of economic crisis with inflation at a record high, usually imports more than half of its wheat from Ukraine. Last Friday, the economy and trade minister, Amin Salam, was reported as saying the country had enough wheat for “a month, or a month and a half.” The government was talking to other suppliers, he added, including the US, “who have expressed their willingness to help if we needed to import large quantities of wheat.”

There is a surplus in the global production of wheat this year, but if you look at where the wheat will be coming from, it means a longer lead time and higher transportation costs.

Abeer Etefa, a World Food Programme spokesperson based in Cairo, said many of the commodities already affected by the Russian invasion were “of particular importance” to the Middle East and North Africa. But sourcing grain from other exporters was not easy, she warned, according to a report in the Guardian.

“There is a surplus in the global production of wheat this year, but if you look at where the wheat will be coming from, it means a longer lead time and higher transportation costs [than from Ukraine],” she said.

In Egypt, where flatbread is a staple food, much of the wheat comes from Russia and Ukraine. Even before the invasion, with prices having risen by 80% between April 2020 and December 2021, the government said it planned to raise the cost of heavily subsidised bread for the first time in decades after President Abdel-Fattah El-Sisi said: “I cannot provide 20 loaves of bread at the cost of one cigarette.”

The Egyptian prime minister, Mostafa Madbouly, said the government would “ensure that the neediest people are not harmed,” but gave no more details. In Lebanon, which also subsidises bread, Salam warned that the central bank would not be able to keep pace if prices continued to rise.

Tunisia’s government remains tightlipped on the flour shortages, even though the evidence is already apparent. Across the country, bakeries are shutting early, or rationing supplies, with anger growing among owners.

“There’s been a problem building for months,” said Hazem Bouanani, a baker. “Normally, we buy flour from mills and the government will reimburse us. For 10 months, we haven’t seen any payment.”

Habib Awaida, at the 80-year-old Sabbat bakery, was stoic, declaring that “even if we can’t find bread, we’ll eat something else.” He added, however, that it was up to the government to reduce Tunisia’s reliance on imports. “We should really think about investing in our own wheat,” he said.

Dr. Bilal Philips

Dr. Bilal Philips