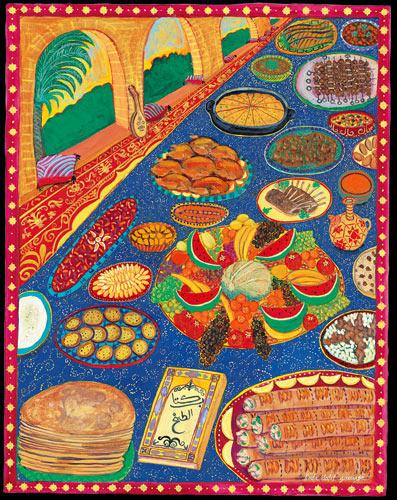

Cooking with the Caliphs:

Food from 9th century Baghdad

A little over a thousand years ago, an Arab scribe wrote a book he titled Kitab al-Tabikh (The Book of Recipes). It was a collection of recipes from the court of ninth-century Baghdad, for the scribe’s unnamed patron—probably Saif ad-Dawlah al-Hamdani, the culture-minded prince of 10th-century Aleppo—had specifically asked him for the recipes of “kings and caliphs and lords and leaders.” The scribe, Abu Muhammad al-Muzaffar ibn Sayyar, was in a position to oblige, being descended from the old Muslim aristocracy himself.

The book has come down to our time in three manuscripts and fragments of a fourth—and what a treasure it is. These are the dishes actually eaten by the connoisseurs of Baghdad when it was the richest city in the world. There are recipes from the personal collections of every caliph from al-Mahdi (died 785) to al-Mutawakkil (died 861), including 20 from Harun ar-Rashid’s son al-Ma’mun. Thirty-five of the recipes—nearly one-tenth of the non-medicinal dishes in the book—come from Harun’s brother, the famous poet and gourmet Ibrahim ibn al-Mahdi.

This was the golden age of medieval cookery; centuries later, cookbooks would still carry recipes named for these very men: haaruuniyyah, ma‘muuniyyah, mutawakkiliyyah, ibraahimiyyah. A dish named for Ma’mun’s wife, buraniyyah, lives on today.

But Kitab al-Tabikh includes scarcely any of the familiar dishes of the modern Arab world. There’s no hummus or tabouli, no stuffed grape leaves, no kibbe, no baklava. Many dishes have strange, clanking medieval names like bazmaawurd, kardanaaj, isfiidhabaaj and diikbariika.

It was a heavily Persianized cuisine, but the dishes are not those of modern Iran either. There isn’t a single pilaf recipe, for example. What we see in this book is the royal cuisine of sixth- and seventh-century Iran along with a wealth of new dishes created under its influence by the chefs of Baghdad.

When the Arabs conquered Persia, they found a sophisticated court with a rich and impressive cuisine, and they eagerly adopted Persian eating habits.

This was inevitable. Pre-Islamic Arabia had a wholesome but monotonous diet that revolved around dates, barley and dairy products. There were separate Arabic words for fresh dates mixed with milk (majii’), dried dates steeped in milk (siq‘al), pitted dates kneaded with milk (watii’ah) and pounded dates moistened with milk (wajii‘ah). When the Arabs conquered Persia, they found a sophisticated court with a rich and impressive cuisine, and they eagerly adopted Persian eating habits.

Kitab al-Tabikh contains anecdotes about cooking contests organized by the Persian kings. We know that the Abbasid caliphs later did the same. And “The Story of King Khusraw and His Page” was eventually translated into Arabic with many details intact, such as the fattening of chickens on hemp seed.

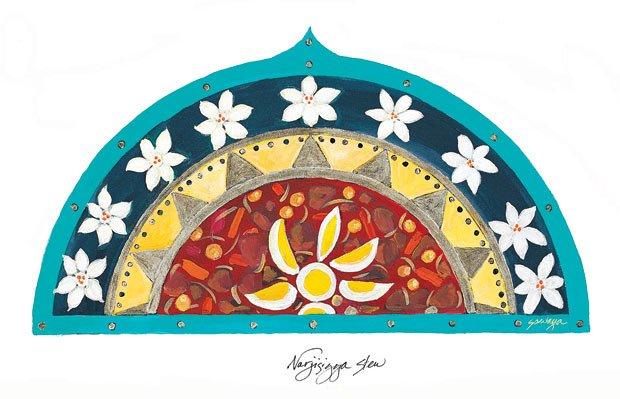

The centerpiece of ninth-century Baghdadi cuisine was rich and complex stews, often cooked in the tannuur (tandoor oven). Some had Persian names, such as sikbaaj (which was flavored with vinegar) and naarbaaj (flavored with pomegranate juice). The dishes with Arabic names, presumably developed in Baghdad, were often named after the main ingredient; for example, ‘adasiyyah (lentils with meat) and shaljamiyyah (with turnips). Some were named for aristocrats, such as haaruuniyyah (containing ground sumac, clearly one Harun ar-Rashid’s favorite spices, because it appears in several of his recipes in Kitab al-Tabikh). A few stews have fantasy names. Narjisiyyah was topped with an egg, giving it the appearance of a narcissus flower—at least, if you really yearned to see the resemblance.

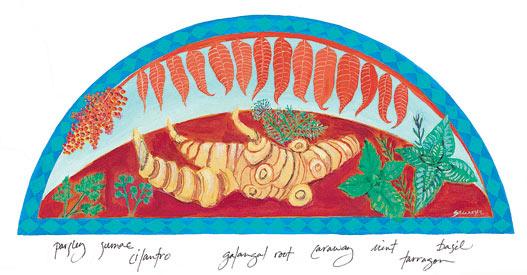

The dishes in this book call for a wide range of spices, including some little used in many Arab countries today, such as caraway (highly popular in the ninth century), the garlic-like asafetida, and galangal, a root which tastes like a cross between ginger and mustard. Fair enough: Everybody knows medieval food was heavily spiced. What’s more surprising is the lavish use of herbs in these recipes—sometimes five or more herbs in a single dish, including basil and tarragon as well as the usual mint, parsley and cilantro of modern Arab cookery. Many stews are sprinkled with the bitter, plum-scented herb rue just before serving. Even more surprising, many medieval stews call for cheese to be thrown in at some point.

The most unexpected flavoring is murri. This was made by wrapping lumps of barley dough in fig leaves so that they would be attacked by mold, then mixing the moldy barley with flour, salt and water and allowing it to ferment for another month or more. The rotted barley paste would then be pressed to yield a dark-brown liquid which turns out to taste just like soy sauce. This whiff of soy ran through the food of the caliphs. The Arab sauce was not borrowed from China, however: Murri was never made from beans and it was always a liquid sauce, while the Chinese product was used as a paste until the 16th century.

It comes as a surprise that eggplant shows up so rarely in these recipes. In today’s Arab world, it is sayyid al-khudaar, the lord of vegetables, but at the time it was a recent import from India and not yet quite popular. It was considered impossibly bitter; in a widely repeated anecdote, a Bedouin declared that eggplant had “the color of a scorpion’s belly and the taste of a scorpion’s sting.” It was actually considered bad for the health. Doctors blamed it for everything from freckles and a hoarse throat to cancer and madness.

Still, there are seven eggplant baaridah in this book, probably because a taste for eggplant first arose among the aristocracy. Two of the dishes are called baadhinjaan buran, “the eggplant of Buran,” after al-Ma’mun’s wife, whose month-long wedding party was a medieval byword for luxury. Today a vast range of dishes called burani or buraniyyah are made everywhere from Spain to India. The recipes in Kitab al-Tabikh, dating from only 50 or 60 years after her death, must be very close to the originals. One is simply fried eggplant slices sprinkled with murri, pepper and caraway. It’s rather good.

Excerpt from an article written by Charles Perry for the Saudi Aramco World. Charles, a former food writer for The Los Angeles Times, has written widely on food history and published a translation of al-Baghdadi’s 13th-century cookbook (A Baghdad Cookery Book, Prospect Books, 2005).

Limited free articles. Subscribe for full access.

Dr. Bilal Philips

Dr. Bilal Philips